PUTTING THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT IN PERSPECTIVE

We recently marked the one year anniversary of the establishment of the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses, and it is appropriate to review our efforts during the past year and to report on our plans for the future.

At the start of the year many at the Defense Department asked, "How did we get into this mess?" The best answer that we can give is that the DoD finds it very hard to deal with battlefield casualties that don’t manifest themselves in traditional ways. The loss of public credibility over Gulf War illnesses follows similar problems with Agent Orange and POW/MIAs after the Vietnam War. In this case, as the crisis over Gulf War illnesses grew, we did not listen to the veterans nor did we provide them with the information they needed to alleviate their fears and answer their questions. Today, much has changed in the way the Defense Department relates to those who served in the Gulf.

We are working very hard to answer the question most frequently asked— "Why are so many veterans sick?" Despite a substantial increase in funds allocated to medical research, we still do not have answers to that basic question. While a careful review of past medical studies, now underway, may yet provide some new insights, recently funded research is not likely to provide answers either quickly or easily.

Even though the causes of unexplained Gulf War illnesses remain elusive, the men and women who served in the Gulf also want and deserve to know if they were exposed to anything that could threaten their health. This question is the unique responsibility of the Department of Defense. We owe it both to the veterans of the Gulf War and to those who serve today to ensure that we learn from the experiences of the war in order to better protect those who will serve in the future.

The following report reviews the events leading up to, and the establishment of, the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses. We highlight four significant changes put in place over this past year and review the more important results of our investigations into possible exposures from chemical or biological agents. We also highlight significant activities with other agencies as examples of the depth of our investigations. Finally, we review what lessons we have already learned and how this work will continue next year.

Put into perspective, our efforts are part of a much broader program by the Administration that has involved a number of offices in the Department of Defense (DoD) and across the Government. We are all committed to President Clinton’s pledge to "leave no stone unturned" in our efforts to care for those who fought in the Gulf War.

The following is a partial list of what we have accomplished during the first year of operations of the Office of the Special Assistant. Most important are the lessons we have learned for the future, and our efforts to change the way the Defense Department does business.

Accomplishments

Major changes were initiated with the establishment of the Office of the Special Assistant:

We are listening to our veterans and incorporating what they tell us into our investigations. We received almost twelve hundred postal letters and twenty seven hundred e-mail letters through the Internet. Our "veteran contact managers" spoke with almost twenty nine hundred veterans by phone.

We have developed an outreach program including GulfLINK and GulfNEWS, and met with veterans at thirteen "Town Hall" meetings and four national veterans conventions throughout the United States. We also frequently meet with Veterans Service Organizations and Military Service Organizations to discuss topics of interest to them.

We are systematically investigating and reporting on possible chemical and biological agent exposures. This includes substantial field testing to determine the likely level of exposure resulting from the detonations of sarin filled rockets at Khamisiyah. We have published four information papers and nine case narratives.

We have extended our inquiries to "other causes" for Gulf War illnesses, such as the fumes from oil well fires, depleted uranium and pesticides.

Lessons Learned

For our efforts to be meaningful, we have to learn from our experiences. Gulf War illnesses, as before it Agent Orange and POW/MIA, represent nontraditional issues that the Department of Defense must deal with in a more effective manner. Specifically, our efforts are helping the Department understand how to build and maintain trust and confidence in the DoD by the American people. Specific to Gulf War illnesses, we need to better account for what happened on the battlefield, and in the future, to better protect our troops on the battlefield from nontraditional risks. Here are some of the things we have learned and are doing:

To build and maintain trust and confidence in the Department, we are institutionalizing our veteran outreach programs to maintain communications with concerned individuals and their organizations.

To better account for what happened on the battlefield, we are developing better time and location data and new programs for retaining, safeguarding and archiving important records, including individual health records.

To protect our troops on the battlefield, we are building better detectors and alarms. We need to initiate better training concerning the inevitability that sensors designed for the maximum protection of our troops will also be prone to false alarm.

Force medical protection has become a significant program of the JCS and OSD Health Affairs. It will be fully implemented and expanded to cover emerging environmental risks.

We will fully implement our programs concerning how to handle hazardous material, including how to handle vehicles struck and contaminated by depleted uranium rounds.

The establishment of the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses was a significant commitment by the Defense Department. While we have made progress during our first year, more has to be done. If our first year is any guide, our programmed work will change as new information is gained from our various studies and investigations. Working with the new President’s Special Oversight Board, to be chaired by former Senator Warren G. Rudman, we hope to complete our inquiries into possible chemical and biological exposures and a number of significant environmental hazards, and can start to draw down the Office. The Department must continue, however, to work with our veterans and their organizations to ensure that we answer their questions and provide them with all the information they need concerning what happened in the Gulf and how it might have affected their health.

EVENTS LEADING UP TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT

Soon after the Gulf War some American veterans, and later a handful from other nations, reported a variety of illnesses and disabilities. One issue raised early in the search for a cause was the possible exposure to chemical or biological agents. In testimony before the Congress, and in press interviews, senior Defense officials asserted that Iraq did not use offensive chemical weapons. To many observers, however, these statements were difficult to reconcile with a number of first hand reports by chemical detection teams, both US and foreign, that chemical agents were present on the battlefield. In the eyes of many in Congress, the media, and many Americans, the DoD was not telling the truth.

In retrospect, the Department was given sage advice by a junior Marine Corps officer in a prophetic recommendation made in an official Marine Corps report on "Marine Corps NBC Defense in Southwest Asia." In the report, then-Captain David Manley noted that:

Survey data indicates that a significant number of Marines believe they encountered threat chemical munitions or agents.... There are no indications that the Iraqis tactically employed agents against Marines. However, there are too many stated encounters to categorically dismiss the presence of agents and chemical agent munitions in the Marine Corps sector (emphasis added).

In 1995, given the inability to come up with answers concerning the causes of the illnesses and the inconsistencies between the statements of senior Defense officials and those who served in the Gulf, President Clinton took decisive action. He established the Presidential Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses (PAC) and ordered the various departments of the Federal Government to reexamine the issues of possible exposure to chemical or biological agents during the Gulf War. The DoD and the CIA initiated new reviews of operational, intelligence and medical records. In March 1995, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense, Dr. John Deutch, established a Senior Oversight Panel, and created the Persian Gulf Illnesses Investigation Team (PGIIT) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs.

In September 1995, a reassessment of information by the CIA indicated Khamisiyah as a possible chemical agent release site. With this new information, the PGIIT was able to determine which troops had been at Khamisiyah. A May 1996 UNSCOM inspection of Khamisiyah documented that 122 mm chemical rockets were in Bunker 73. In June 1996, the DoD announced that it was likely that American troops had unknowingly destroyed sarin-filled 122 mm rockets in March of 1991 at Khamisyah.

In September 1996, the new Deputy Secretary of Defense, Dr. John White, referred to Khamisiyah as a "watershed," and asked Dr. Bernard D. Rostker, Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Manpower and Reserve Affairs), to put together a team to look at everything the Department was doing concerning Gulf War illnesses. We examined all aspects of DoD’s program and concluded that DoD’s then current effort was overwhelmed by Khamisiyah. An example of this was that while the PGIIT had established an 800 hot line to give those who served in the Gulf an opportunity to tell their story, they were unable to follow-up these initial phone reports. By September 1996, they had a backlog of more than twelve-hundred phone reports. It was clear to us that we needed a broader focus, an expanded effort, and a strategy for systematically examining the various theories concerning the nature and cause of Gulf War illnesses. We also needed a plan to effectively communicate DoD’s findings to our veterans and the American people.

On November 12, 1996, Dr. White directed the establishment of the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses with broad authority to coordinate all aspects of the Department’s programs. Dr. White concluded that the Department had not placed sufficient emphasis on the operational aspects of the war and the implications of those operations. He asked that we put a special focus on the operational issues and issues of future force protection of our troops. He emphasized the need to ensure that we had a communication program to reach out to the veterans and to try to learn from them what went on during the war. Responsibility for health related programs, specifically the clinical program and the health research program, remained with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health Affairs.

ESTABLISHING THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT

The Office of the Special Assistant was designed around a three part "Mission Statement" (Figure 1) which emphasized our commitment to our service personnel and veterans who served in the Gulf, and focused on operational impacts on health and future force protection.

Figure 1

The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs continued the specific responsibility to care for our service men and women still on active duty, while the Department of Veterans Affairs is the primary health care provider for those who have left the service. We included, however, "care of those who served in the Gulf" in our mission statement to remind us that the health of our people must come first. With this focus, we worked with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs to make sure that reservists received the full health care and compensation benefits they were entitled, and where current legislation and rules were inadequate, to work towards changing the law and directives.

Our mission charges us to do everything possible to understand and explain Gulf War illnesses, to inform the Gulf War veterans and the American public of our progress, and then to ensure that DoD makes whatever changes are required in equipment, policy and procedures. This is not limited to just the possibility of chemical and/or biological agent exposure, but includes a broader inquiry into such possible causes of illnesses as adverse reactions to vaccinations and/or pyridostigmine bromide (PB), as well as such potential health threats as pesticides, depleted uranium (DU), oil well fires, and even fine sand.

With our mission statement to guide us, we needed to quickly increase DoD’s effort. We selected a number of contractors who provided the flexibility, expertise, and support needed to create the new organization. We should note that outstanding assistance was provided by OSD Administration, the DoD Comptroller and the General Counsel. We borrowed people from OSD Legislative Affairs and OSD Public Affairs, the National Imaging and Mapping Agency (NIMA), and the Services. When we finished, our team was a mix of DoD civilians, active duty military, and contractor personnel, many of whom were veterans themselves. Figure 2 is the organization chart for the new office

Figure 2

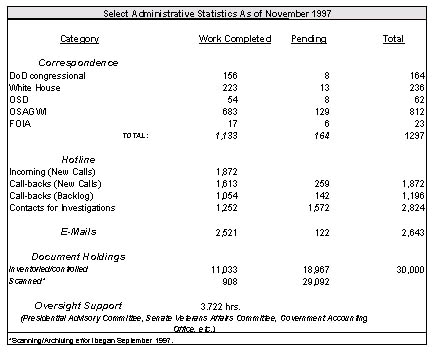

The new organization incorporated a Public Affairs section to coordinate outreach to the veterans’ community and to develop and implement our communications strategy; a Legislative Affairs section to coordinate all testimony and focus our relations with Congress; and, a Legal Office to provide legal advice on FOIA, Privacy Act, copyright and other legal issues. A Quick Reaction team was established to respond to high priority issues such as the Dugway demolition tests that will be discussed later. An Administrative Section was established to manage GulfLINK and the many documents we must handle, as well as the challenge of responding to all correspondence sent to DoD and the White House on Gulf War illnesses. Table 1 provides selected statistics for the past year that highlight the diverse and sizable administrative tasks the new office has completed.

The Medical - Health and Benefits Collaboration office works with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and other health related organizations such as Veterans Affairs, Health and Human Services, and the Persian Gulf Veterans’ Coordinating Board. We provided a viewpoint different from the traditional medical community, and, along with OASD(HA), have been able to ensure that research proposals that are important to the Government’s overall strategy of answering the concerns of Gulf War veterans were fully addressed and funded.

.

Table 1

The core of our effort is the Investigation and Analysis Directorate (IAD), which investigates events surrounding possible causes of illnesses and publishes results as case narratives and information papers. This division is also responsible for our 800 hotline and our phone outreach program.

A NEW WAY OF DOING BUSINESS

In building the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses, we needed to make some major changes from the earlier efforts. First, we had to do a better job of listening to our veterans’ concerns and problems, and incorporating what they were telling us into our investigations. Second, we needed to develop an outreach program in order to effectively communicate with our veterans. Third, we needed to significantly expand the formal investigation process for researching possible chemical and biological agent exposures. And fourth, we needed to expand our investigations beyond chemical and biological agents to include other potential causes of Gulf War illnesses.

First Change: Listening to our Veterans

Our first change was to listen to our Gulf War veterans –the people who were actually in the Gulf and who are in the best position to shed light on the events of the war. We created the Veterans Data Management Division in the Investigation and Analysis Directorate (IAD), staffed by trained "Contact Managers" (CMs), all of whom are veterans and all of whom work directly with the individual Gulf War veterans. Today, within 48 hours of their initial report to our 800 hotline, veterans are fully debriefed by a CM. The CM becomes the primary point of contact between the veteran and our office. Since this is often the first time the veteran has spoken to anyone from DoD about their experiences in the Gulf, the phone conversations often take several hours. We try to answer the questions that the veterans have long wanted answered and to provide information about on-going efforts, including referral information for those needing support from DoD or the VA.

The CMs are the eyes and ears of our investigators, and ensure that the veterans’ full accounts are folded into the analysis. They have interviewed veterans who called the hotline, or responded to surveys and indicated that they may have information needed in our studies, or who contacted our office through letters and e-mail. The CMs have attempted to reach all those twelve hundred veterans whose initial calls to PGIIT had been unanswered; they have been successful in all but one-hundred forty-two cases, where they have not been able to develop a valid phone number. All in all, our contact managers have talked to almost thirty-nine hundred veterans during the last year.

Second Change: Developing an Outreach Program

We immediately established an "open door" policy with the media, veterans groups, Congressional staffs, and the PAC. We began holding regular meetings with Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs)/Military Service Organizations (MSOs) to address their questions and concerns. We have hosted VSO/MSO meetings on such topics as chemical alarms and reconnaissance vehicles, depleted uranium, and medical record keeping.

Starting in March 1997, and working with the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion, we began a series of "Town Hall" meetings to update the veterans on our progress and to hear first hand of their concerns. To date, we have visited fifteen cities (thirteen town hall meetings and four national conventions) as shown in Figure 3.

GulfLINK has been a great success. Typically, we get over sixty thousand home page "hits" in any given week, and we peak at over ninety thousand hits per week during important times such as when we announced the results of our analysis of fallout from the explosions at Khamisiyah. We are very proud that GulfLINK was recently awarded the Government Computer News Agency Award for excellence in the application of information technology to improve services delivery.

We recognize that many veterans do not have Internet access and, to reach them, we developed a bi-monthly newsletter, GulfNEWS, with a current circulation of more than seven thousand and growing.

We also realize that veterans want to know about our investigations as they pertain to their own Gulf War experiences. Therefore, in addition to publicizing our findings in the case narratives, we write to each affected veteran, providing a synopsis of our findings. To date, we have sent more than 150 thousand letters to Gulf War veterans concerning possible exposure to chemical agents. In the case of Khamisiyah, we have told those receiving letters that they may have been briefly exposed to low levels of sarin. In all other cases, however, we have been able to tell veterans that it was unlikely they were exposed, or that they were definitely not exposed.

Figure 3

Third Change: Investigating and Reporting on Possible Chemical and Biological Agent Exposures

We expanded and intensified our efforts to investigate incidents, and to report them to the American people. The resulting "Case Narratives" report on our investigations into possible exposure of our troops to chemical and biological agents. Corollary "Information Papers" provide background material—such as the strengths and limitations of chemical alarms and detection equipment—which helps the reader to better understand the findings reported in the Case Narratives. We have published nine case narratives and four information papers.

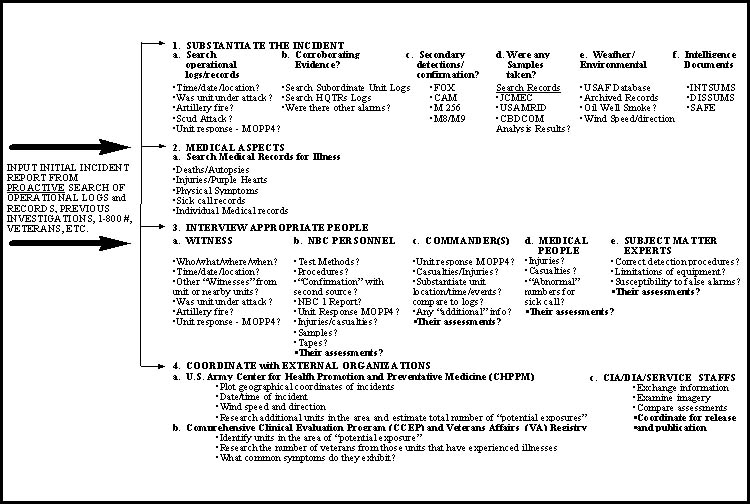

We devised our methodology from chemical agent investigation and validation standards developed by the United Nations and the international community. A case always starts with a report of a possible chemical or biological exposure, usually from a veteran. As illustrated in Figure 4, we seek to identify all of the information that might be available about any particular incident. However, given the passage of time since the Gulf War, we have found it to be difficult to obtain certain types of documentary evidence, and we know that physical evidence was often not collected at the time. Therefore, we cannot apply a rigid template to all incidents, and each investigation is tailored to its unique circumstances.

Our investigations include information from first-hand witnesses who provide valuable insight into the conditions surrounding the incident and the mind-set of the personnel involved—particularly important where physical evidence is lacking. We interview NBC officers and personnel trained in chemical and biological testing, confirmation, and reporting to determine how the involved unit may have responded at the time, what tests were run, whether any known injuries were sustained, and what reports were submitted. We ask commanders for their perspective; what did they know, what decisions did they make, and what was their assessment of the incident. Where appropriate, subject matter experts also provide opinions on the capabilities, limitations, and operation of technical equipment, and submit their evaluations on selected topics of interest.

Figure 4

Case narratives contain the facts that we have been able to find concerning a suspected incident. In a separate section, we provide our assessment of these facts and make a judgment concerning the presence of chemical or biological agents. The sections are separated to make clear what is fact and what is opinion.

Even after intense investigation, information from various sources may be contradictory. Thus, we use a five part assessment scale that ranges from "Definitely" to "Definitely Not," with intermediate assessments of "Likely," "Indeterminate," and "Unlikely" to describe how our analysts appraise the information. While the assessment often gets the most attention, it is the least important part of the case narrative. The purpose of the case narrative is to get all the facts before the American people. We believe the credibility of our work lies with the quality and completeness of our investigations.

Since we recognize that we may not have all the facts, case narratives are interim reports. Figure 5 is a typical case narrative cover sheet. It highlights a 1-800 telephone number so that veterans can call and provide additional information that will enable us to report more accurately on the events being investigated. Final reports will be issued only when we are satisfied that we have exhausted all avenues in our search for information and can tell the complete story of a specific event or issue.

Figure 5

During the months ahead, we will continue to investigate and publish a number of additional case narratives and information papers relating to various reports of chemical and biological agent use, detection, and exposure. These investigations will cover, among other topics, reports of chemical injuries, suspected chemical agent storage sites, and reported detections of chemical agents. We are committed to looking into any incidents that may shed light on why our veterans are sick.

Fourth Change: Extending the Inquiry to "Other Causes" for Gulf War Illnesses

Much attention has been paid to the possible exposure of Gulf War veterans to chemical and biological agents. However, these are only two of many adverse exposures that could have impacted the health of those serving in the Gulf. Therefore, we have initiated a number of other studies into the various environmental factors and unique occupational risks to which our veterans may have been exposed.

The first "environmental" studies, now in progress, address the exposure of our troops to depleted uranium, oil well fires, and pesticides. These studies differ significantly from our work on specific chemical incidents. They are not designed to assess the likelihood that our troops were exposed to a specific agent at a specific place and time, but rather to a more general understanding of the hazards faced by our forces.

However, exposures are only half of the puzzle. To complement our examination of what happened during the Gulf War and to allow us to assess the possible health risk impacts of a number of factors, we need to better understand the state of medical science. RAND, a federally funded research and development center, was commissioned to prepare reviews of the existing scientific literature on eight of the possible causes of illnesses among Gulf War veterans. Each will be peer-reviewed by independent scientists who are distinguished in their fields, and each will be accompanied by a separate summary written specifically for the veterans. RAND is producing reviews on the following topics which are scheduled for release in early 1998:

Chemical and biological warfare agents

Immunizations

Pesticides

Pyridostigmine bromide

Stress

Infectious disease

Fallout from oil well fires

Depleted Uranium

We believe that these four changes, together with a substantial increase in DoD resources, gives us the ability to answer many questions veterans have asked. The next section highlights the case narratives and information papers that report what we have learned.

CASE NARRATIVES AND INFORMATION PAPERS OF POSSIBLE CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL AGENT EXPOSURES

Since the publication of our first case narrative dealing with Khamisiyah last February, we have published four information papers and eight additional case narratives. (The full reports are available on GulfLINK.) The information papers published are:

Mission Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP) and Chemical Protection, November 13, 1997

M8A1 Automatic Chemical Agent Alarm, November 13, 1997

Medical Surveillance During Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, November 13, 1997

The Fox NBC Reconnaissance Vehicle, July 29, 1997.

Case Narratives published are:

Tallil Air Base, Iraq, November 13, 1997

Fox Detections in an ASP/Orchard, September 25, 1997

Al Jaber Air Base, September 25, 1997

Reported Mustard Agent Exposure Operation Desert Storm, August 28, 1997

Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia, August 13, 1997

Possible Chemical Agent on SCUD Missile Sample, August 13, 1997

These reports, published on GulfLINK, range in size from the 96 page Al Jubayl report—which covered three incidents in Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia, in early 1991—to a 10 page analysis of possible chemical agents on a piece of SCUD missile. Each report cites numerous source documents, hyper-linked to footnotes in the case narratives.

Taken together, the case narratives and information papers start to provide a picture of what really happened to US and coalition troops during Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm, and the months after the war. The picture, however, is not complete and must be filled in by the additional case narratives that will be published in the months ahead.

The most significant case narratives, thus far, are the one about Khamisiyah, and the collection of case narratives concerning the possible presence of chemical agents in Kuwait.

Our inquiry has focused on two questions: what happened at Khamisiyah and why did it take so long for the DoD and CIA to realize chemical munitions were destroyed there in early March 1991?, and who was exposed to what level of sarin as a result of detonating stacks of chemical-filled 122 mm rockets in the open pit at Khamisiyah?

What Happened At Khamisiyah And Why Did It Take So Long For The DoD And CIA To Realize Chemical Munitions Were Destroyed There In Early March 1991?

The story of Khamisiyah is told in two reports by the DoD and the CIA, and independently corroborated by the Army Inspector General’s investigation. (All three reports have been posted on GulfLINK.) We have described Khamisiyah as an enigma: how could there have been a major chemical incident when, as the Army IG reported, "no chemical weapons were detected during the operation itself [and] units neither knew nor suspected that they were destroying chemical munitions." Without contemporaneous operational or medical reports, investigators were skeptical about initial UNSCOM and Iraqi accounts that US forces had destroyed chemical weapons at Khamisiyah. In addition, a review of the testimony and responses to questions by DoD in 1994 before the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee (the Riegle Committee) shows how confused DoD witnesses were about the location of Khamisiyah and its proximity to US troops. DoD analysts continued to believe that any destruction of chemical munitions probably had occurred after the war as part of an Iraqi deception campaign.

Credit for correctly putting the pieces of the puzzle together goes to the CIA. This is how it is explained in the CIA report (which is available on GulfLINK):

Because of the increased focus on Gulf war illness issues by both the public and Congress, as well as concerns raised by two CIA analysts, Acting Director of Central Intelligence Studeman authorized a comprehensive review of intelligence by CIA on the issues related to the Gulf war in March 1995. ... possibility that US forces could have been exposed to fallout from US bombing of Iraqi CW production and storage facilities. As part of this study, a CIA analyst constructed a comprehensive summary of Iraqi CW-related facilities, focusing on the status and disposition of CW agents at these sites. … The Khamisiyah facility emerged as a key site that needed to be investigated because of its proximity to Coalition forces and the ambiguities surrounding the disposition of chemical weapons at the site. CIA informed DoD's Persian Gulf Investigative Team (PGIT) in September 1995 of Khamisiyah's importance and requested additional information about US troop activities there to which PGIT responded in October....

CIA and DoD personnel met with UNSCOM officials on 19 March 1996. ... UNSCOM indicated that it planned to revisit Khamisiyah to resolve newly raised munitions accounting issues.... At the 1 May 1996 PAC meeting, CIA publicly announced that the 37th Engineering Battalion had destroyed munitions at Khamisiyah in March 1991 and that CIA was ‘working with the DoD Investigative Team to resolve whether sarin-filled rockets were destroyed at Bunker 73 and whether some US personnel could have been exposed to chemical agent.’ During UNSCOM's inspection of Khamisiyah on 14 May 1996, it was determined that some of the destroyed rockets in Bunker 73 were chemical weapons. ... DoD publicly announced ... [that US forces destroyed chemical weapons in Bunker 73 and at the "pit"] ... on 21 June 1996.

Who Was Exposed To What Level Of Sarin As A Result Of Detonating Stacks Of Chemical-Filled 122 Mm Rockets In The Open Pit At Khamisiyah?

In order to estimate who may have been exposed to sarin as a result of detonations of rockets at the "pit" area of Khamisiyah, we needed to know who was where, how much chemical agent was released by the explosions, and where the agent went. None of this information was directly available. For example, in order to determine who was near Khamisiyah the Army hosted a number conferences of former operations officers (S-3/G-3s) from the XVIII Airborne Corps and VII Corps to determine where their units were during the early part of March 1991. Before these conferences began, the Army had 233,756 known unit locations, mostly battalions and larger formations. As a result of these conferences, we now have more than twice that number of unit locations for company size units.

We worked to reduce other uncertainties regarding the demolition at Khamisiyah. Together with the CIA, we undertook extensive ground testing at the Army’s Dugway Proving Grounds to determine the effects of detonating stacks of chemical-filled 122 mm rockets in the open. We built new computer simulation models by linking old models that incorporated weather information with chemical agent transport models. By combining the results of all of these efforts, we were able to estimate the units most likely to have been exposed and the levels of that exposure. People in those units were individually notified by letter of their possible exposure to low levels of nerve agent.

Approximately one hundred thousand American troops and an unknown number of coalition and Iraqi troops may have been exposed to low levels of sarin as a result of detonating stacks of chemical-filled 122 mm rockets in the open pit at Khamisiyah on 10 March 1991. In July, we notified those who were most likely exposed that

Current medical evidence indicates that long-term health problems are unlikely. The Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs are committed to gaining a better understanding of the potential health effects of brief, low level nerve agent exposures, and they have funded several projects to learn more about them.

In September and October, we briefed our coalition partners in the Czech Republic, France, the United Kingdom, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Egypt and offered to help determine which of their troops may also have been exposed. (We also briefed the Israelis during our trip to the Middle East.)

In total, there have been six reports issued on Khamisiyah by the Office of the Special Assistant and the CIA. An additional report, recently released by the Army Inspector General, substantiates our findings concerning the events that took place at Khamisiyah. Work on the Khamisiyah story continues with a revised case narrative incorporating all the work done this year, technical reports on the Dugway demonstration and analytic modeling, and a Congressionally mandated report, due in March 1998, on lessons learned by DoD from intelligence operations at Khamisiyah.

Several other case narratives deal with Marine Corps operations and other reported exposures in Kuwait, which were the subject of testimony before the PAC and Congress. To date, we have traced Marine operations through the minefield at the border of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, to Al Jaber Air Base and on to an ammunition supply point in an orchard near Kuwait International Airport. Our assessment in each of these cases is that it is "unlikely" that chemical agents were present. We have not said "definitely not present" because some data or information is missing, like the Fox reconnaissance vehicle tapes.

Other cases address several separate incidents at the Port of Al Jubayl that were believed by some veterans to be chemical agent exposures, and a Fox vehicle detection at Camp Monterey after the war. The Al Jubayl incidents were assessed as "unlikely" that chemical warfare agents were present. Our assessment of the event at Camp Monterey is that nerve or mustard agents were "definitely not" present. Analysis of the Fox vehicle tape showed the substance detected at Camp Monterey to be CS, a riot control agent.

To date, the results of our investigations are consistent with the information provided by other governments. In England, and again in Kuwait, government officials told us that the contractors hired after the war to clear mines in Kuwait never reported finding any chemical mines or other chemical munitions, even though it would have been to their financial advantage to make such a report. In addition, UNSCOM testified before the PAC on July 29, 1997 that

In the period from 1996 to 1997 the Commission has undertaken to investigate further the history of the production, filling and deployment of the 155 millimeter mustard shells and also the 122 millimeter sarin rockets.... We now believe Iraq deployed 155 mm mustard rounds and 122 mm sarin rounds during January of 1991…[to] Aukhaider, Nassiriyah, Khamisiyah and the Mymona depot.... We have seen no evidence ... that [weapons were moved from the three lower depots, actually down into Kuwait].

However, we are still piecing this puzzle together incident by incident, and do not yet have a complete picture. Much more work remains to be done before we can say that fallout from the Khamisiyah demolition was the only chemical exposure (albeit low level) our troops suffered while in Kuwait.

SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES WITH OTHER AGENCIES

During this year, our office was engaged with other agencies in a number of significant activities that illustrate the type of investigations we have undertaken, the thoroughness of these investigations, and the size of the Government’s commitment to "leave no stone unturned." These illustrative activities are:

The Army IG’s investigation of what happened at Khamisiyah.

The re-creation of the events at Khamisiyah.

The DoD IG’s investigation of the missing CENTCOM Chemical Logs.

The declassification of important documents relating to possible

chemical or biological exposures.

Army IG’s Investigation Of What Happened At Khamisiyah.

At the request of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Army directed the Inspector General of the United States Army to conduct an inquiry to determine the facts surrounding the demolition of ammunition at the Khamisiyah Ammunition Storage Facility in March 1991. The following is an extract from the report of the Army Inspector General, which is on GulfLINK.

The Department of the Army Inspector General [DAIG] Inquiry Team gathered and assessed over 2000 pages of documents and support materials, to include orders, reports, photographs, video tapes, and operational logs of appropriate CENTCOM units. Visiting twelve major installations, including some located in Korea, Japan, and Germany, the Team interviewed over 700 soldiers, veterans, and civilians, collecting over 300 photos and numerous copies of personal logs and notes. Of the approximately 430 individuals involved in the Khamisiyah demolition operation, the Team interviewed about 250 of them. Coordination was made with agencies ranging from the CIA/DIA to the Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses.

The DAIG Team developed a detailed timeline of the Khamisiyah demolition operation, concluding that no chemical weapons were detected during the operation itself and that force protection measures were generally adequate, although not all soldiers performed to standard when an M8 alarm sounded on 4 March 1991.

The DAIG Team found no empirical evidence that chemical munitions/agents were present during the demolition operation. The Team found no conclusive evidence that US Army ground units either knew or suspected that they were destroying chemical munitions. Physical evidence found later by UNSCOM, supported by a review of available imagery, photos, and intelligence, led the intelligence community and various investigative bodies concerned with Khamisiyah to conclude that chemical munitions were present when the facility was destroyed. The Team likewise found no conclusive evidence that supported or refuted the conclusions of the intelligence community/other investigative bodies.

Re-creation Of The Events At The Khamisiyah "Pit"

DoD and CIA, together with the US Army, worked to estimate the amount of chemical warfare agents released from the Khamisiyah pit. Part of this was extensive field tests at the Army’s Dugway Proving Ground and the Edgewood facility in Maryland. The following is extracted from a joint report by CIA and DoD on the Dugway and Edgewood tests which can be found on GulfLINK.

During last year's modeling efforts, we noted that without ground testing we could not estimate with any degree of certainty the amount of agent released at Khamisiyah or the rate of release. In the 1970s, the US conducted additional testing on US chemical rockets to characterize the impact of terrorist actions. Unfortunately, the US tests did not measure the amount of airborne agent downwind and did not help quantify probable release parameters. Thus modelers of the pit demolition were unable to assess whether the agent would be released nearly instantaneously or over a period of days. The later scenario obviously was more dependent on weather conditions.

To resolve these uncertainties, CIA and DoD agreed in April 1997 on the need to perform ground testing before a meaningful computer simulation could be completed. We cooperated to design and implement a series of tests in May 1997 at the Dugway Proving Grounds, which gave us a much better understanding of the events at Khamisiyah. DoD provided complete logistic and administrative support for the tests.

The testing involved a series of detonations of individual rockets and some in stacks, with high-explosive charges placed the way soldiers say they placed them in March 1991. This was done to resolve questions like: how did the rockets break? what happened to the agent? were there sympathetic detonations? how much agent might have been released? We could not replicate the entire demolition of hundreds of rockets, but we did gain information critical to our modeling efforts.

First, we took special care in replicating the rockets in the pit, including:

Using 32 rocket motors identical to those detonated in the pit.

Manufacturing warheads based on detailed design parameters provided by UNSCOM, including precise wall thickness, materials, and type of burster tube explosive.

Building crates based on precise measurements and UNSCOM photographs.

Choosing a chemical agent simulant, triethyl phosphate, that closely simulates the volatility of cyclo-sarin and is often used as a simulant for sarin.

Stacking the rockets as described by soldiers involved in the pit demolition.

We performed six tests at Dugway using the 32 available rockets. We began with four tests on single rockets in preparation for tests involving nine and 19 rockets. We included a few dummy warheads to increase the size of the stacks. Finally, one of the unbroken rockets from the multiple tests was dropped from an aircraft to simulate a flyout.

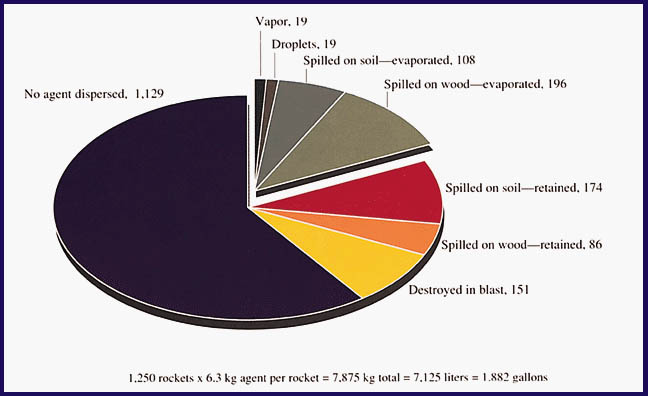

The results were very revealing. The only warheads that burst and aerosolized agent were those that had charges placed just beyond the nose of the warhead. Only the warheads immediately adjacent to the charges leaked agent. Even the rocket dropped to simulate a flyout did not disperse any simulant; it buried itself over 30 feet below the surface. The pie chart in figure 6 shows the distribution of agent from these tests among aerosolized vapor and droplets, spill into soil and wood, burning, and unaffected. Only about 32 percent of the agent was released, mostly leaking into the soil and wood. A total of 18 percent became part of the plume—two percent through aerosolization and 16 percent through evaporation (5.75 percent from soil and 10.4 percent from wood).

Figure 6

The Dugway testing provided a physical basis for estimating the effect of a charge on the surrounding rockets. We used pressure sensors to refine our gas dynamics models to approximate the threshold forces required to break a warhead. Gas dynamics modeling of the detonations and resultant pressure waves further bolstered our confidence that the results of the Dugway testing were realistic. This allowed development of a model to determine the effect of various placements of charges and orientations of rockets:

Charges were placed on the ends of rockets opposite the embankment. (As cited in interviews with US soldiers.)

Charges broke adjacent warheads but not warheads at the other end. (Dugway field testing)

Evaporation in accordance with Dugway laboratory testing of a 3:1 mixture of sarin/cyclosarin agent at a temperature of 14 degrees C.

Number of rocket flyouts is low (fewer than 12) with probability of leakage from the rockets minimal. (Soldier interviews and Dugway testing).

We feel confident that the model paradigm is consistent with UNSCOM information, soldier photos, and conservative assumptions. For example, the proportion of rockets whose agent was not affected during our ground testing (56 percent) closely matched the 708 filled rockets UNSCOM found after the demolition (56 percent). Also, examination of the three known post demolition pit photos of the rockets show very little damage with only 4 out of 36 rockets (11 percent) showing obvious damage.

The large percentage of agent leaking into the soil and wood increased the importance of additional work conducted at Dugway and Edgewood laboratories. The tests were initially planned at Dugway and Edgewood to be performed on soil but, on the basis of the Dugway ground testing results, were expanded to include wood. These tests began by spilling the sarin and cyclosarin mixture onto wood and soil, respectively, and then measuring the rate at which the agent evaporated. The tests also were designed to closely replicate conditions in the pit, including:

Sarin and cyclosarin—not simulants—were used in a 3:1 ratio.

Soil, including some from Iraq, which was assessed to be similar to pit sand, was obtained for the tests. We tested pine, a common wood used for 122-mm rocket boxes.

Tests simulated the wind speeds most likely present during the pit demolitions. Different temperature ranges were used to cover the range of daytime and nighttime temperatures in the pit.

The results of the Dugway laboratory tests ... [show that] most of the chemical warfare agent evaporated during the first 10 hours. Thereafter, with a significantly decreased surface area from spillage, the release was slow, and significant portions of the agent stayed in the soil and wood. In addition, tests of [Khamisiyah type] soil at Edgewood indicated that about one-eighth of the agent degraded in the soil in the first 21 hours.

DoD IG’s Investigation Of The Missing CENTCOM Chemical Logs

On March 3, 1997, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed that the Inspector General, Department of Defense, assume responsibility for an investigation begun in January 1997 by the Office of the Special Assistant to locate missing US Central Command (CENTCOM) Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) desk logs maintained in the Joint Operations Center (JOC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, during the Persian Gulf War. The following is a extract from the report of the DoD Inspector General which is on GulfLINK.

When we assumed control of this investigation from OSAGWI, we learned that investigators from the OSAGWI had compiled an extensive investigative record on the issue of the missing logs. This included interviews of approximately 40 individuals. In-depth interviews of the six NBC officers had been conducted in the January-February 1997 time frame. Also, in late February 1997, OSAGWI investigators visited CENTCOM and conducted interviews of current and former CENTCOM personnel who may have been in possession and/or control of the logs. During that visit, they conducted an office-to-office search of desks and cabinets within CENTCOM, and examined computers and computer disks that may have contained the logs.

This investigation was conducted by the Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS), the criminal investigative arm of the DoD IG. Significant investigative actions included: conducting approximately 185 interviews and a number of polygraph examinations; execution of 3 search warrants; execution of 2 command directed searches at CENTCOM and Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG), MD; document searches by DoD and non-DoD Agencies and organizations; forensic examination of 4 computers and approximately 100 computer disks; the review of more than 700 boxes containing approximately 700,000 pages of archived records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); and the review of more than 22,000 pages of CENTCOM FOIA files.

Based on our investigative effort, we reached the following conclusions:

We did not recover any additional pages of the missing logs, in either hard copy or computer form. However, we recovered a significant number of log entries some of which we believe were copied from the still missing pages of the logs. These log entries are contained in the "Log Extracts," which we recovered during a search of personal effects belonging to an Army officer who previously had access to the logs and who is currently under criminal investigation in connection with this matter.

The most probable explanation for the missing logs, which were returned to CENTCOM, MacDill Air Force Base, Tampa, in April 1991, is that they were destroyed. This probably occurred in October 1994 or later, after the downsizing and relocation of the CENTCOM J3 NBC office, and after a complete rotation of personnel including original NBC officers who served in the JOC in Saudi Arabia.

Despite considerable effort, the computer disk purportedly containing a copy of the logs returned to APG, MD, in March 1991, could not be located.

The suspected computer virus that reportedly occurred in the CENTCOM JOC during December 1990 was determined by NSA not to be a computer virus, but a software recognition problem. Even if a computer virus had occurred at that time, as reported, it should not have had an effect on logs created and maintained after the offensive operations commenced on January 17, 1991, and when chemical and biological exposure incidents most likely would have occurred. Therefore, no missing log entries or pages appear to be attributable to a computer virus.

Although directives, regulations and internal CENTCOM J1 (Administration) memoranda required that Gulf War records be retained, safeguarded and archived as permanent records, the logs, in their entirety, were not safeguarded and archived by CENTCOM.

Our investigation found no credible evidence to support a conspiracy to willfully and wrongfully destroy or dispose of the logs in violation of either the Uniform Code of Military Justice or Title 18, United States Code.

Army’s Declassification Of Important Health Related Documents

Since March 1995, the Army has been DoD’s Executive Agent for the declassification of Gulf War operational records. As Executive Agent, the Department of the Army provided guidance and coordinated the DoD effort to locate, gather, and review operational records in order to "identify all information pertaining to health problems experienced by veterans of the Persian Gulf War." *(DIA, CIA and other agencies also had ongoing declassification efforts for intelligence documents).

Each Service issued multiple records calls to ensure that all existing Gulf War operational records were located and collected. The records collected from major headquarters units throughout the services are comprehensive and reasonably complete. However, gaps existed for many smaller units. Therefore, the Army sent search teams to installations with a high density of units that deployed to the Persian Gulf. These search teams went to installations located both in the continental United States and US Army Europe. Further, video-teleconferences were conducted with installations with a low density of units that deployed to the Persian Gulf. As a result of this effort, approximately 560 thousand additional documents were found.

The declassification procedures utilized by the services included state of the art document imaging systems to scan and store Gulf War era records into an electronic database. DoD collected over 6.4 million classified records.

These records were searched, 1.1 million were identified as possibly health related, and were forwarded to the OSAGWI team for use in their investigation. Concurrently, these 1.1 million records were further analyzed by the Services and, after eliminating duplicates, records not containing health related information, and mismatches with key words, over 54 thousand were determined to be actually health related and were declassified and placed on GulfLINK. Table 2 shows the breakout of documents by component.

All components listed in Table 2, except for the Air Force, have reported "mission complete." Although the Air Force completed the initial illness tasking in December 1996 as originally mandated by the DEPSECDEF, they are not able to declare full "mission complete" on the overall tasking because new material continues to be found in DoD channels which needs to be reviewed. Along with reviewing all operational Gulf War records for possible declassification and release, the Air Force is also collecting personnel information for inclusion in the US Armed Services Center for Research of Unit Records Gulf War Registry database, and reviewing and cataloguing 1300 video tapes (both Air Force and non-Air Force) received from the Defense Visual Information Center. All services have the capability and are prepared to respond to Gulf War declassification requirements as they arise. In the course of our investigation, we routinely identify material from investigators needing declassification to be used in our narratives. This material is forwarded to the appropriate agency for declassification and returned for our use.

Table 2

For our efforts to have meaningful value, we have to go beyond just investigating and reporting on possible chemical or biological exposures, or even environmental or occupational hazards. We have the responsibility to learn from our experience in the Gulf, including how we handled the post-war investigations. What we have learned can be placed into three groups:

How to build trust and confidence in DoD

How to better account for what happened on the battlefield

How to better protect our people on the battlefield

How To Build Trust and Confidence in DoD

At the start of this report we answered the question, "How did we get into this mess?" by saying: "The best answer that we can give is that, as the crisis over Gulf War illnesses grew, we did not sufficiently listen to the veterans, nor did we provide them with the information they needed to alleviate their fears and answer their questions."

We also noted admonitions that we should not "categorically dismiss" claims that our troops were exposed to chemical agents. In fact, this is the third time in recent history that the Department has had to mount a concerted effort to investigate claims after our credibility has been called into question. The previous times concern POW/MIA and Agent Orange from the Vietnam War.

First, we need to be able to provide a full accounting of what happened on the battlefield. This will be discussed below. Second, this accounting cannot just come from the medical establishment. While the veterans are most often concerned about their health, the answer to many of their questions cannot be provided by health professionals alone. Key information can only be provided by those in charge of units in the field. Third, and more importantly, we need to establish and sustain viable communications with concerned individuals and their organizations. As this report shows, investigations are only one part of the many activities of this organization. It is vitally important for the Department to retain credibility with the veterans’ community. Reaching out and being responsive to the needs of our veterans is a very important part of our effort and here is the primary lesson regarding credibility: DoD should institutionalize a veterans outreach capability after we have completed our investigations and the Office of the Special Assistant is disestablished.

How To Better Account For What Happened On The Battlefield

The DoD has an absolute responsibility to be able to tell our service members what likely happened on the battlefield, what they may have been exposed to, and the likely health consequences of those exposures. Re-creating historical events after the fact is always difficult, especially when critical information was not collected and we are not able to retrieve important records.

Time and Location Data

A significant problem has been the lack of data showing where individuals or units were located at any given point in time. Such data is key to determine who may have been exposed to harmful agents, whether in Vietnam, the Gulf, Haiti, Bosnia or some future deployment area. After the Gulf War, Congress mandated that DoD construct a data base to identify where people were during the oil well fires. This was later expanded to track troop locations throughout the theater. The initial efforts, started in 1993, retrieved over six million field records to search one at a time for references to time, place and unit identity. The data base was mainly of battalion-size units. We found this data not specific enough to identify those who may have been exposed to fallout near Khamisiyah in March 1991. Working with the Army, we brought together the former operations officers (S3/G3s) from division and brigade size units to validate the unit location registry and to provide additional company location information from deployment to redeployment. In July 1997, we completed the daily tracking of XVIII Airborne Corps units. We expect to complete the same for VII Corps units and all units under Army Central Command (ARCENT) and its support command by February 1998.

This effort, however, only allows us to know where unit headquarters were located. It does not tell us where individual soldiers were on any given day or during fast moving operations. Collecting such data from hundreds of thousands of soldiers may not be as daunting a task as first seems, given modern electronics and GPS. We asked the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a federally funded research and development center, to investigate the possibility of a non-intrusive battlefield data collection system. They recently published a paper, "Full Dimensional Protection: The Personnel Tracking, Records and Reports Dimension," that identifies significant shortfalls in the Services ability to track the movement of individuals and units on the battlefield and suggests actions to cover these gaps which will be provided to the DoD for appropriate action.

Retaining, Safeguarding And Archiving Of Important Records

Our inability to retrieve records has been both frustrating and a significant factor in the Department’s loss of credibility. The efforts by the DoD IG to locate the missing CENTCOM Chemical Logs is an example. The damage done to the credibility of the Defense Department cannot be overstated. Last January, the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee held public hearings to ask General Norman Schwarzkopf if he knew about Khamisiyah, and to review his personal papers to determine if there had been any reference to any chemical incidents during the period that pages from the CENTCOM Chemical Logs were missing. Today, we know from the Army IG’s investigation that units at Khamisiyah "did not detect the presence of chemical munitions or chemical agents during the demolition operation [and] made no reports of such a detection." We only know of the presence of chemical agents at Khamisiyah after the fact from UNSCOM, and recent reviews of imagery, photos, and intelligence, as a result of investigations by DoD and the CIA. We also know from the DoD IG’s investigation that there is "no credible evidence to support a conspiracy to willfully and wrongfully destroy or dispose of the logs." Many of these inquiries would have been unnecessary if the log pages had been properly archived, as required. Currently, there is no uniform records management program for Joint Commands. Each command follows the rules and procedures of its host Service at its headquarters installation. The Joint Staff has taken on this issue and established a CINC’s Record Management Program to "fast track" the development of new policies and procedures.

Unfortunately, the case of the CENTCOM Chemical Logs is but one example of missing records. We will never know exactly how many records were actually generated and can never accurately estimate how many operational records might exist. Each Service has different regulations concerning the generation, maintenance and disposal of records. Despite numerous requests to search for and forward records, the Army’s field visits this year found over one-half million pages of Gulf War era documents that had previously not been reported. CENTCOM also recently discovered documents that have not previously been identified.

There are many organizational factors that have contributed, over the years, to the lack of unit level records, especially turbulence associated with the drawdown during the early 1990s. In the Army, force structure reductions and a desire to maximize the number of soldiers dedicated to warfighting vis-�-vis administration led to the elimination of the company journal, or "morning report", and the company clerks in favor of battalion level administration. This means that records today are less available than they were during World War II or the Korean War. The Army’s Force XXI program, a major initiative aimed at transitioning the force into the next century, should provide better record keeping in the future.

How To Better Protect Our People On The Battlefield

The Gulf War has been the subject of numerous studies and many lesson learned exercises. A selection of these are available on GulfLINK. We, too, have identified a number of things that need to be changed as a result of our inquiry into Gulf War illnesses. Many changes are already underway, but many still need to be made. Changes can be categorized into these groups:

Chemical and biological equipment, especially detectors and alarms

Medical force protection

Education concerning the handling of hazardous material

Chemical And Biological Equipment, Especially Detectors And Alarms

One of the most significant issues arising from the various inquiries concerning possible chemical detections during the Gulf War concerned the prevalence of false alarms. On the battlefield, false alarms often increased the anxiety among our troops and often resulted in troops either ignoring the alarms or turning them off altogether. When we started our investigations, it was generally understood that M-8 alarms were prone to false alarm, but it was also thought that the Fox NBC Reconnaissance Vehicle with its MM-1 Mobile Mass Spectrometer could not false alarm. (Information Paper is posted on GulfLINK.) Several Fox vehicle crew members testified before Congress and the PAC concerning readings they obtained and questioned why their chain-of-command did not believe that chemicals agents were present. Our case narratives clearly explain how a Fox vehicle could generate a false alarm or a false positive reading. The manufacturer, Bruker Analytical Systems, Inc., noted in a letter assessing the false positive report at Camp Monterey that "Since the standard procedure calls for taking a complete spectra and verifying the identification, some false alarms in Air Monitor mode are accepted by the Army to INSURE that there are NO FALSE NEGATIVES where a dangerous agent such as Sarin would not be detected." (Emphasis original) Unfortunately, a complete spectra was almost never taken and Fox Vehicle tapes were almost never retained. Therefore, to confirm that chemical agents were present, it is more often necessary to have confirmatory evidence. In fact, MITRE noted in their "Chapter 11" report (also on GulfLINK) that "in the absence of reported casualties, detections of Sarin vapor reported by the Fox mass spectrometer system in proximity to troops, must be interpreted to imply that (either) only protected personnel (in MOPP4) were in the vicinity of the Fox vehicle when the MM-1 spectrometer detected the Sarin and/or the Sarin detections were in error either because of interferents (e.g. oil well fire smoke) or equipment malfunction."

While we note that there have already been several changes to the Fox vehicle, such as replacing the silicone collection wheels with materials that did not result in false alarms for Lewisite, and other changes are planned such as the installation of the Global Positioning System (GPS) and the addition of the M-21 stand-off chemical detector, there is still no doctrinal requirement to collect and safeguard MM-1 spectrometer tapes.

In the case of the M-8 alarm, many chemical compounds used in either a normal or a military operational environment (i.e. diesel, gasoline exhaust, burning fuel, etc.) can cause this system to false alarm. (Information paper is posted on GulfLINK.) Additionally, operating in unusual or severe environmental conditions, for which the system was not designed, could also cause false alarms. For example, during the Gulf War, high temperatures and sand concentrations often caused this system to false alarm. Operating in unusual or severe conditions can drain the system’s power sources, especially the batteries. In turn, low batteries can cause a false alarm. Based on inputs from commanders and lessons learned from Desert Storm, improvements will be incorporated into the M22 Automatic Chemical Agent Detector Alarm (ACADA) which will begin replacing the M8A1 Alarm System in March 1998. This new detector will sense both nerve and mustard agent vapors, and is expected to have fewer false alarm responses to many known interferents—especially gasoline and diesel exhausts.

Force Medical Protection

Force medical protection during the Gulf War was implemented in varying degrees, but was neither standardized nor centralized among deployed forces. For

example, in September 1990, the Navy established a laboratory, known as the Navy Forward Laboratory (NFL) at the Marine Corps Hospital in Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia. The effort was supported by the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, and drew upon many assets (people, equipment, expertise) from several Navy medical research and preventive medicine activities OCONUS and CONUS. (The story of the Navy Forward Laboratory is available in an information paper on medical surveillance on GulfLINK.) The NFL developed into a state-of-the-art infectious disease diagnostic laboratory that had the capabilities of a well-equipped laboratory in CONUS. When fully operational, the NFL became a theater-wide, infectious diseases reference laboratory. Other Services, however, did not establish similar facilities in theater.

After the war, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and the Joint Staff undertook a complete review of doctrine, policy, oversight and operational practices for medical surveillance and force medical protection. Changes were applied to subsequent deployments to Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti, and Bosnia, and modified accordingly. Recently, OSD/Health Affairs and the Director of the Joint Staff announced the development of a comprehensive force medical protection strategy. This approach to force medical protection throughout the deployment continuum has been adopted within Presidential Review Directive NSTC-5, "Development of Interagency Plans to Address Health Preparedness for and Readjustment of Veterans and Their Families After Future Deployments." Joint publications are being revised to reflect changes in doctrine. Theater operations plans are being revised to include appropriate force medical protection measures. Ultimately, of course, support of force medical protection programs is the responsibility of theater and joint task force commanders.

One very important change will be the new Personal Information Carrier (PIC), a small dog-tag-like computer storage device that will store medical information, including patient history, treatments, and vaccination records. Historically, medical record keeping has been less than perfect, especially during deployments. One very frustrating issue with veterans is their inability to retrieve their medical records. At best, in their view, this makes it difficult to establish a service connection on health claims, and, at worst, it is added proof that the Department is withholding critical information. The PIC will be only one part of a full electronic theater medical record system to ensure that medical records are not lost.

Individual health information between the VA and DoD is currently incompatible. Creating the ability to electronically transfer data between the two Departments and/or creating a database that is compatible with the VA’s would be of benefit to the veterans and could reduce the cost associated with adjudication of claims. Through a joint DoD/VA Executive committee, a number of initiatives are underway. One is to set up procedures for the transfer of a wide range of health information, regardless of whether or not the respective data systems are compatible. A second initiative is to agree to a common discharge physical and the medical information collected as part of the physical. The third is to jointly acquire a computerized patient record system that would be used by both Departments.

In addition to these actions, Deputy Secretary of Defense John White commissioned a special advisory panel of the National Academy of Sciences to review and advise DoD on our medical force protection program. Their work is just getting underway.

Education Concerning How to Handle Hazards Materials

Our investigations into potential health hazards of depleted uranium (DU) point to serious deficiencies in what our troops understood about the health effects DU posed on the battlefield. These hazards were well documented as a result of the Army’s exhaustive developmental process for fielding DU munitions. Unfortunately, this information was generally known only by technical specialists in nuclear-biological-chemical health and safety fields. Combat troops or those carrying out support functions generally did not know that DU contaminated equipment, such as enemy vehicles struck by DU rounds, required special handling. Similarly, few troops were told of the more serious threat of radium contamination from broken gauges on Iraq’s Soviet-built tanks. The failure to properly disseminate such information to troops at all levels may have resulted in thousands of unnecessary exposures.

On September 9, 1997, we wrote to the chiefs of the Air Force, Navy and Marines encouraging them to "ensure that all Service personnel who may come in contact with DU, especially on the battlefield, are thoroughly trained in how to handle it." The requirement for training extends beyond the normal basic and technical training and should be provided to all members of the force. We are currently working with the Joint Staff to ensure that all service personnel who might come into contact with DU (e.g., combat and support personnel and anyone deployed to a theater where DU might be used) receive appropriate training on how to handle DU and DU contaminated equipment.

PUTTING THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT IN PERSPECTIVE

The Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses has accomplished a great deal this year; however, we are not the only organization addressing Gulf War issues. Throughout the Government, many have made significant efforts and deserve to be recognized.

The Presidential Advisory Committee stimulated DoD to improve its efforts and provided oversight which led to a review of our standards and methods. Although we have had our differences, we recognize their dedication to helping our veterans.

The Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs) shares with us the common mission to ensure our service men and women receive the care they need. Health Affairs maintains the Comprehensive Clinical Evaluation Program, which provides medical examinations to our veterans. Additionally, they manage the Department’s Gulf War related medical research program, and, with the JCS, they have the lead in the medical force protection program

The DoD Inspector General’s investigation into the missing CENTCOM nuclear, biological and chemical logs and the Army Inspector General’s investigation into the events at Khamisiyah were important independent efforts.

The Assistant to the Secretary of Defense (Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Defense Programs) provides expert advice on chemical and biological warfare issues, especially on the tests at Dugway Proving Grounds.

The Assistant Secretaries of Defense for Legislative Affairs and for Public Affairs and their staffs provided invaluable support.

The DoD Comptroller has provided the resources needed to undertake a complete and through investigation.

The Army’s support has been outstanding from the declassification project implementation of a state-of-the-art facility to review, declassify, and archive documentation, to organizing the S3/G3 conferences.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Health and Human Services worked with us through the Persian Gulf Veterans’ Coordinating Board to address interagency solutions, especially on medical research.

The Central Intelligence Agency and the Defense Intelligence Agency have been valued partners working with us on a daily basis in our common search for answers.

Most importantly, the National Security Council Staff has coordinated the work of all government agencies in a very effective manner. The Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Gulf War Illnesses issues has provided outstanding leadership.

This has truly been a Government-wide effort. We have all adhered to the President’s charge to "leave no stone unturned," not just because he told us to, but because we are all dedicated to do whatever it takes to support those who served so bravely during the Gulf War.

Establishing the Office of the Special Assistant was a significant commitment by the Defense Department to the Government-wide effort to support those who served in the Gulf War. Significant progress was made during our first year in investigating specific claims that our troops were exposed to chemical agents, and to better understand the events and fallout from the demolitions at Khamisiyah. As we look ahead, the following are the planned and on-going activities that will take us into our second year:

Complete and publish as "interim reports" twelve additional chemical case narratives, three additional information papers and updates to two previously published case narratives.

Complete and publish three reports each on pesticides, depleted uranium (DU) and the fallout from oil well fires. My office will review what happened in the Gulf and identify a number of likely "exposure scenarios." The Army’s CHPPM will attempt to estimate the possible dose rate for each of the exposure scenarios. RAND will review what medical science says about the danger from these exposures.

Complete our investigation of the Air Campaign, including a detailed analysis of possible fallout using the same models used to estimate the fallout from the Khamisiyah demolitions.

Conduct an analysis of Army in-theater hospital records.

Conduct an extensive inquiry into the possibility that Iraq used biological warfare agents.

Exploit contacts made during our Middle East trip, particularly with the Saudi Arabian National Guard concerning research on any changes in the health status of the indigenous Saudi population after the Gulf War

Expand our outreach program to cover the "Total Force;" those currently on active duty and members of the National Guard and Reserve components.

Monitor programs in place as a result of lessons learned to date; e.g., DU training by the Services, as well as the continuing effort to archive and declassify health related Gulf War documents

IDA will complete research into low level chemical doctrine and publish several papers applicable throughout DoD.

RAND will complete and publish eight medical reviews, as well as two papers on management of our medical program.

Several medical research projects we have been monitoring closely will report during our second year. Most notable being the review of Dr. Garth Nicolson's techniques for detecting the presence of Mycoplasma fermentans (incognitus strain).

The S3/G3 conferences will be completed by the end of February 1998. As a result, we will be better able to determine the number of personnel exposed to low level chemical agents at Khamisiyah. We will also incorporate information about the location of Air Force personnel.

If our first year is any guide, additional reviews will come up during the year that cannot now be anticipated. We look forward to the challenges ahead and to working and cooperating with the President’s Special Oversight Board to be chaired by former senator Warren G. Rudman. I expect, by the end of next year, that we will have completed all major investigations into possible chemical and biological exposures and a number of significant environmental hazards, and can start to draw down the Office of the Special Assistant. A residual effort will be needed to continue to meet the needs of our veterans, e.g., to continue GulfLINK and other outreach programs, and to maintain a focal point in the Department of Defense on issues of Gulf War illnesses.